Knots in traditional art

Origins of knots in traditional art[edit]

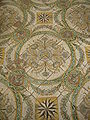

Ornamental knot work, or interlacing, in the decorative arts of Europe and the Middle East originated in the Roman Empire during the third and fourth centuries AD. These beginnings can be seen particulartly in many Roman floor mosaics of that time.[1]

Previous to the developments of Rome, early uses of knots are found in some Egyptian symbols, particularly in the Tyet or Isis knot, and in the Sema which represents the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. Knots are also frequently found represented in the Egyptian Cartouche and the Ankh.

Ancient Egypt[edit]

Roman mosaics[edit]

Byzantine art[edit]

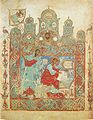

-

before 512

Celtic art in pagan and Christian times[edit]

J. Romilly Allen (1847-1907) published Celtic art in pagan and Christian times in 1904. The book is a scholarly study of Celtic art, and is still often cited as an important source on the subject.

Coptic art[edit]

Syriac orthodox Mor Gabriel Monastery (Turkey)[edit]

Mor Gabriel Monastery (also known as Dayro d-Mor Gabriel) The Monastery of St. Gabriel) is the oldest surviving Syriac Orthodox monastery in the world. It is located on the Tur Abdin plateau near Midyat in the Mardin Province in Southeastern Turkey.

Medieval period (British Isles)[edit]

Ireland[edit]

Stone crosses[edit]

Church ornamentation[edit]

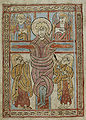

Illuminated manuscripts[edit]

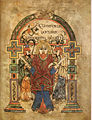

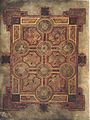

Book of Kells[edit]

Lindisfarne Gospels[edit]

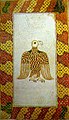

Book of Durrow[edit]

Lichfield Gospels[edit]

Stowe Missal[edit]

Artifacts[edit]

Wales[edit]

Scotland[edit]

England[edit]

Isle of Man[edit]

Medieval period[edit]

Illuminated manuscripts[edit]

-

before 512

-

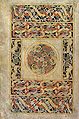

Ireland, 8th century

-

Carolingian, 8th century

-

Carolingian, 8th century

-

France, 9th century

-

c.950-975

-

10th century

-

10th century

-

10th century

-

11th century

-

France, 1190-1200

-

France, 12th century

-

12th century

-

13th century

-

12th century

-

c. 1390-1410

-

14th century

-

14th century

-

France, 14th century

-

c. 1389-1400

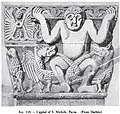

Church ornamentation[edit]

Renaissance[edit]

Illuminated manuscripts[edit]

Architectural ornaments[edit]

Leonardo da Vinci emblem[edit]

By country[edit]

Armenia[edit]

Church ornamentation[edit]

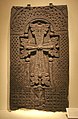

Khatchkars[edit]

Although not as well known as Irish 'Celtic' crosses, khatchkars represent an art tradition that deserves attention.

Illuminated manuscripts[edit]

Ethiopian Crosses[edit]

Georgia[edit]

Germany[edit]

Iceland[edit]

Israel[edit]

Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, Jerusalem[edit]

Augusta Victoria[edit]

Church of All Nations (Jerusalem)[edit]

Dominus Flevit Church[edit]

Church of Mary Magdalene[edit]

Italy[edit]

Spain (Galicia)[edit]

Kuba[edit]

Kuba people[edit]

Nigeria, Benin Kingdom[edit]

Norse art[edit]

Oseberg style[edit]

Borre style[edit]

Jelling style[edit]

Mammen style[edit]

Ringerike style[edit]

Urnes style[edit]

Mjolnir[edit]

Valknut[edit]

Viking[edit]

Stave church ornamentation[edit]

Grave orbs[edit]

Russia[edit]

Islamic interlace patterns[edit]

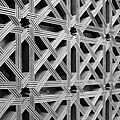

Geometric interlacing patterns are a subcategory of Islamic pattern and ornament, and are a particular type of arabesque. Historically, the origins of the Islamic interlace patterns are from the more simple interlace patterns of late Roman and Byzantine mosaics[2]. One of the first Western studies of the subject was E. H. Hankin's "The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art", published in Memoirs of the Archaeological Societry of India in 1925.[3]

According to Eva Baer, in her book Islamic Ornament:

....the intricate interlacings common in later medieval Islamic art, are already prefigured in Umayyad architecture revetments: in floor mosaics, window grilles, stone and stucco carvings and wall paintings(Khirbat al-Mafjar, Qusayr'Amra, Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi etc.), and in the decoration of a whole group of early east Iranian, eighth- to tenth-century metal objects.[4]

Examples of geometric interlacing can also be found in Arabic calligraphy, particularly designs made in in the Square Kufic style.[5]

Owen Jones, in his catalog for the Crystal Palace exhibition, wrote about the decorative art found in Alhambra, where much of the art work consists of interwoven designs, that:

The grace and refinement of Greek ornament is here surpassed. Possessing, equally with the Greeks, an appreciation of pure form, the Moors exceeded them in variety and imagination.[6]

Design methods[edit]

E. H. Hankin, in his book The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art, takes the view that the artists who created these designs used a method based on the use of the compass and the straight edge.[7] This view is supported by the majority of contemporary authorities on the subject, such as Keith Critchlow in his book, Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach.[8] This explains how ornamented objects as varied in size as a book or a mosque, were treated by artists using the same geometric methods adopted to the size and nature of the object being ornamented.[9]

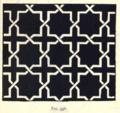

On the other hand Owen Jones, in The Grammar of Ornament, describes a different construction method whereby this type of interlace ornament is, instead, designed based on a foundation of geometric grids; with the same foundational grids re-drawn to the size of the object.[10]

-

Basmala in kufic calligraphy

Synagogues[edit]

Ostia Antica, Italy[edit]

Florence, Italy[edit]

Toledo, Spain[edit]

Córdoba, Spain[edit]

Segovia, Spain[edit]

Tzippori, Israel[edit]

Susya synagogue[edit]

Knot gardens[edit]

Knots in heraldry[edit]

In an English heraldic blazon, anything knotted, such as a rope, serpent or lion's tail, is described as nowed.

Knotted serpents[edit]

Nagas[edit]

Nāgas are a group of serpent deities in Hindu and Buddhist mythology.

Knotted dragons[edit]

Jain[edit]

Aztec[edit]

Caduceus[edit]

The caduceus a symbolic object representing the Greek god Hermes (or the Roman Mercury), and trades or occupations associated with that god.

Knots in pattern design books[edit]

A Handbook of Ornament[edit]

Franz Sales Meyer's book, A Handbook of Ornament (published in 1849), collected examples of ornamental art from a variety of traditional sources. Meyer's drawings usually suggest possible construction methods for the designs.

Traditional Methods of Pattern Designing, Archibald Christie[edit]

Archibald H. Christie: Traditional Methods of Pattern Designing. An Introduction to the Study of Formal Ornament, Oxford: Clarendon Press 1910.

Cusack's Freehand Ornament[edit]

The Anatomy of Pattern, Lewis Foreman Day[edit]

Knots in art by shape[edit]

Endless knot[edit]

Solomon's knot[edit]

Triquetra[edit]

Others[edit]

Alchemy[edit]

Chinese traditional decorative knots[edit]

This is a traditional craft, originating in the Tang Dynasty (618–907AD), and continuing to the present day.[11].

Love spoons[edit]

Maiolica floor tiles[edit]

Maiolica is Italian tin-glazed pottery dating from the early Renaissance. This type of pottery is particularly suited to painted surface decoration.

Rangoli and Kolam[edit]

Rangoli and Kolam are a traditional artform of India, made by women with dry colored powders on floors inside houses, or outside the house. Because they are made with dry powders they are temporary.

Vanuatu sand drawing[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ James Trilling, The Language of Ornament (Thames and Hudson 2001), p.134-136

- ↑ James Trilling (2001). The Language of Ornament. Thames and Hudson Ltd ISBN 0-500-20343-1

- ↑ "The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art", "Preface"

- ↑ Eva Baer Islamic Ornament p.41. New York University Press, 1998 ISBN0-8147-1329-7

- ↑ [1] Mamoun Sakkal, How to design Square Designs in Square Kufi

- ↑ Iain Zaczek quoting Owen Jones, in his annotation of Owen Jones' The Grammar of Ornament, p.206

- ↑ E. H Hankin, The Drawing of Geometric Patterns in Saracenic Art, p.2

- ↑ Keith Critchlow, Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach, p.9

- ↑ Daud Sutton, Islamic Design: A Genius for Geometry, Walker Publishing Company, 2007. p. 1. (ISBN- 10: 0-8027-1635-0)

- ↑ Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament, p.72-73

- ↑ Lydia Chen, Chinese Knotting (Echo Publishing Co. 1982) p.27