Commons talk:Licensing/Archive 38

| This is an archive of past discussions. Do not edit the contents of this page. If you wish to start a new discussion or revive an old one, please do so on the current talk page. |

Scans/Photos from books in copyright

These are two images that people have scanned from books and put in the public domain. Yes, the artists themselves are more than 100 years old, but the books are recent and copyrighted. I don’t think scans of photos from books (unless the books themselves are old) are eligible for free licensing, and in any case, they have been screened for publication to 300dpi and therefore are not very useful anyway. Delete them?

- File:Woven_silk,_Western_Han_Dynasty.jpg

- File:Horse_of_Han_Wudi.Western_Han_dynasty._Maoling_Museum.jpg

I suggest a line be put in the Tutorial "What's not allowed in Commons": scans or photographs of illustrations in books in copyright Gleeb (talk) 10:57, 11 May 2014 (UTC)

- If a public domain photograph is put in an otherwise copyrighted book, the copyright status does not change. It's still a public domain photograph. We would not care about the copyright status of the rest of the book, just what is uploaded. If those photos are indeed licensed OK, then yes they are indeed useful (as borne out by their wide usage on wikipedias). No scope issue. Now... we have to get back to the question of the photographs. The pictured works of art are very old, but photographs usually have their own separate copyright, and that needs to be licensed (this is the part which may feel wrong to you... a modern photograph of an old work). File:Woven_silk,_Western_Han_Dynasty.jpg might be a {{PD-Art}} situation. Not as straightforward as a painting, but the photo may not have enough creativity to qualify for copyright. If not, the scan is OK. Somewhat debatable. As for File:Horse_of_Han_Wudi.Western_Han_dynasty._Maoling_Museum.jpg, the photograph definitely has a copyright and we need a license for it. There is a claim of "own work", but if that refers to the scan of the photograph (which is what it seems like), then that is not OK and it should be nominated for deletion. Carl Lindberg (talk) 16:46, 11 May 2014 (UTC)

- DR created: Commons:Deletion requests/File:Horse of Han Wudi.Western Han dynasty. Maoling Museum.jpg, and yes, the other one may be PD-Art. Regards, Yann (talk) 18:58, 11 May 2014 (UTC)

OLD picture postcards

How old postcards have to be, to freely use a scan ?--Stillo (talk) 09:04, 18 May 2014 (UTC)

- It depends. ;oD

- For European postcards, the basic rule is 70 years pma, and many postcards are signed. So you have to find who is the photographer, or show that they are not signed (also look at the back).

- For US postcards, everything before 1923 is OK. Regards, Yann (talk) 13:38, 18 May 2014 (UTC)

- Essentially, a postcard is no different from any other published image. Hchc2009 (talk) 18:07, 18 May 2014 (UTC)

Licenses {{PD-old-100}} and {{PD-old-90}} have text "This work is in the public domain in the United States, and those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less." {{PD-old-80}} and {{PD-old-75}} use similar text but without claim of PD in US. {{PD-old-70}} use similar text except that substitutes "European Union" for US. I looked at Commons:Hirtle_chart and could not find anything that justify the change of the text between {{PD-old-80}} and {{PD-old-90}} to claim PD in US. Also if {{PD-old-100}} was sufficient in US than we would not need {{PD-old-100-1923}} and {{PD-old-100-1996}}. I would like to propose to replace {{PD-old-100}}, {{PD-old-90}}, {{PD-old-80}} and {{PD-old-75}} main message with text from {{PD-old-text}} used by {{PD-old-auto-1923}} template family. That would unify the language and provide a single place for translations. --Jarekt (talk) 14:38, 19 May 2014 (UTC)

- I support your proposed change for {{PD-old-80}} and {{PD-old-75}}. However, I'd suggest that {{PD-old-100}} and {{PD-old-90}} need slightly different handling. I would support your proposed change to {{PD-old-90}} if you also add the "also include a United States public domain tag / note about Mexico" warning from {{PD-old-80}} when changing the main message.

Unfortunately, {{PD-old-100}} is a special case because of history between Commons and English Wikipedia. On en.wp en:Template:PD-old is "PD in US plus life+100" while on Commons {{tl|PD-old} has been "life+70" (it's been deprecated for a long time though), so in the past {{PD-old-100}} was often recommended as the replacement for en.wp's PD-old when moving content to Commons from English Wikipedia. This license transform may still be in place in some of the Commons transfer tools. I would support your proposed change to {{PD-old-100}} only if you both add an "also include a United States public domain tag" warning and propose a plan for updating the hundreds of thousands of images that are only tagged with PD-old-100 to instead use {{PD-old-100-1923}} or {{PD-old-100-1996}}. —RP88 19:06, 19 May 2014 (UTC)

- An additional thought — I would not be averse to the idea of introducing {{PD-old-100-not-us}} (or perhaps call it {{PD-old-100-source}}) that clones {{PD-old-100}} but includes your proposed changes along with an "also include a United States public domain tag" warning. Along with your other proposed changes this could be used in place of {{PD-old-100}} in the implementation of {{PD-old-auto}}, fixing the current weirdness of {{PD-old-auto}} where it starts claiming the tagged work is PD in the U.S. when the years since the death of the author reach or exceed 100. —RP88 19:58, 19 May 2014 (UTC)

- {{PD-old-100}} is a special case. For example, I have no idea how to check the publication history of this Leonardo da Vinci self-portrait which would be needed for evaluation of its US copyrights, but the assumption is that it is in PD in US as well as in the rest of the world. However the fact that we assume PD in US does not mean that {{PD-old-100}} should claim PD in US. If we can replace {{PD-old-100}} with {{PD-old-100-1923}} or {{PD-old-100-1996}} we should, but in most cases PD-old-100 images are paintings or sculptures in which case I have no clue what "publishing" means. I do not see any chance for successful "plan for updating the hundreds of thousands of images that are only tagged with PD-old-100 to instead use {{PD-old-100-1923}} or {{PD-old-100-1996}}", since if I it is not clear how to do a single one we will not be able to convert thousands of them. I also do not see how the fact that en:Template:PD-old is wrong is relevant to corrections on Commons. "PD-old" templates there (and here) are often used without much thought, for files that "must be too old" for copyrights, like this file.

- As I said, I would like to propose to replace {{PD-old-100}}, {{PD-old-90}}, {{PD-old-80}} and {{PD-old-75}} main message with text from {{PD-old-text}} which is used by {{PD-old-auto-1923}} template family. I was not planning on changing the "notes" and warning portions of those licenses, but we could use the warning Template:PD-old-70 uses.--Jarekt (talk) 13:37, 20 May 2014 (UTC)

- I'll address your points one at a time:

- Regarding the Leonardo da Vinci self-portrait, a reproduction appears in Del Cenacolo di Leonardo da Vinci by Giuseppe Bossi, published in 1810. I'll update the image license to {{PD-old-100-1923}}.

- Regarding your statement that {{PD-old-100}} should not claim PD in US, I agree in principle that this is awkward, but that doesn't change the fact that it has claimed so for many years and countless uploaders have undoubtedly relied on its statement of "PD in US AND life+100" when they chose it to apply to an upload.

- Regarding how "publishing" applies to objects like paintings or sculptures, see Commons:Publication and (for the U.S.) Commons:Public art and copyrights in the US. Basically, the U.S. considers works that have been placed in a public location without restrictions on copying prior to 1978 to be published (after 1978 such works are only published if tangible copies of the work have been distributed to the public).

- With regards to your claim that en:Template:PD-old is wrong, I have to disagree. While it is true that license tag may well have been misapplied on en.wp to many images, there is nothing inherently wrong about it being a "PD in US AND life+100" license tag.

- Only two of the PD-old-N tags lack the "also include a United States public domain tag" warning, namely {{PD-old-100}} and {{PD-old-90}}, presumably due to their origin as "PD in US and life+N" tags. I do think if you change the main message to the one from {{PD-old-text}} you need to add warnings to these two, however the warning from Template:PD-old-70 would not be correct. The warning from Template:PD-old-80 would be fine for {{PD-old-90}}. The warning from Template:PD-old-80 without the comment about Mexico and Côte d'Ivoire would be fine for {{PD-old-100}}, if we go through with that change.

- In summary, I think you've misunderstood my concern. I am very supportive of your idea to clean up the weird inconsistencies in the PD-old-N tags, I'd be happy to assist you in the effort if you'd like. My only concern is {{PD-old-100}}. Every PD image on Commons needs a US copyright tag and a source copyright tag (if of a non-US origin). Some PD tags are only source tags (i.e. PD-old-70), some are only US copyright tags (i.e. PD-1923), and some are both (i.e. PD-old-70-1923). For odd historical reasons, PD-old-100 has been a "both" tag, despite this being inconsistent with the other PD-old-N tags. I would not be surprised if thousands of images on Commons were tagged with PD-old-100 with the understanding that it was a "PD in both US and source" tag. Admittedly, I would not be surprised at all if there are also thousands of images tagged with PD-old-100 only because of the years since the death of the author, with no thought given to the US copyright status (despite the PD US claim in the current text of the tag).

- If we change the main message of {{PD-old-100}} to the text from {{PD-old-text}}, many thousands of images will no longer have a claim of PD in the US, despite that claim being there at the time the uploader chose it for the license. These images would suddenly, because they now lack a PD US claim, be potentially eligible to be nominated for deletion. If you want to change the text, one possible plan for dealing with existing images tagged only with PD-old-100 (instead of changing them to either PD-old-100-1923 or PD-old-100-1996) would be to, at the very least, get community consensus that while all new uploads tagged with the new version of PD-old-100 would also need a PD US tag, old uploads would be "grandfathered" and not immediately be eligible for deletion. —RP88 16:42, 20 May 2014 (UTC)

- I'll address your points one at a time:

- Thank you for the link to Commons:Publication, I added it to bunch of licenses wherever word "publish" is mentioned. That way It will be easier to find in the future.

- About en:Template:PD-old and {{PD-old-100}} I do think they are wrong since 100 years from author's death does not make work PD in US, as the template implies. It also does not change anything in US legal status from lets say 99 or 70 years from author's death. However it seems to me that most {{PD-old-100}} files are either:

- unpublished and can use {{PD-US-unpublished}};

- were published in the author's lifetime (before 1923) and can use {{PD-1923}}, or

- were published outside of US in years 1923-1978 and can use {{PD-1996}}.

- So most {{PD-old-100}} works are also PD in US - we just do not know why.

- I hear your concern about {{PD-old-100}}, that "Every PD image on Commons needs a US copyright tag and a source copyright tag (if of a non-US origin)". And if there were some people tagging files with {{PD-old-100}} that were thinking about US copyright they did not share those thoughts with us and did not use more specific tags. I for example changed many thousands {{PD-old}} to {{PD-old-100}} if creator died more than 100 years ago and transcluded {{Works of authors who died more than 100 years ago}} template. I do not worry about mass deletions of {{PD-old-100}} files if we remove the US part: we do have thousands of {{PD-old}} or {{PD-old-70}} files unaccompanied by US specific tags, and they are "grandfathered" in.

- If you would like to help you can tackle updating warnings in the PD-old-X templates. In the mean time I am trying to unify wording and help with translation of many of our templates by use of {{PD-old-text}}, {{PD-1923-text}}, and {{PD-1996-text}}. I am also looking at multitude of overlapping templates that are used for PD works, see Commons:Multi-license copyright tags and trying to cut down on number of parallel solutions. --Jarekt (talk) 13:23, 21 May 2014 (UTC)

- Thanks for taking the time to discuss this with me. You've convinced me that changing the text on {{PD-old-100}} will be OK; hopefully if this triggers any deletions this discussion can be pointed to regarding "grandfathered" status of these images. If you change the text on {{PD-old-100}} and {{PD-old-90}} I will add the appropriate "needs US copyright tag" warning. I guess we still disagree about how to interpret the meaning of the current text of en:Template:PD-old and {{PD-old-100}}. When I read these I don't interpret a meaning of "This work is PD in any country whose copyright term is life+100 and because of this it is PD in the US", instead the meaning I interpret is "This work is PD in the US (for an undisclosed reason). This work is also PD in any country whose copyright term is life+100 or less." —RP88 13:42, 21 May 2014 (UTC)

- The wording of en:Template:PD-old and {{PD-old-100}} is a little like en:My Wife and My Mother-in-Law drawing, you either see one or the other but it is hard to see both. I always interpreted the text as "This work is in the public domain in the United States, and other countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 100 years or less." just like {{PD-old-70}} text where EU replaces US. But you are right it is ambiguous. May be {{PD-old-100}} "note" section should have invitation to use {{PD-old-100-1923}}, {{PD-old-100-1996}} or {{PD-US-unpublished}} (which should be probably merged with {{PD-old-auto}} to create {{PD-old-auto-unpublished}}, if we have enough files using it). The "note" of PD-old-XX files should advise the use of PD-old-auto, if used directly. --Jarekt (talk) 14:39, 21 May 2014 (UTC)

Copyrights on vector images of "simple designs"

Under the "Simple design" section, it is mentioned that simple designs (i.e. logos) which are either too simple for copyright or old enough that the copyright has expired are accepted on Commons even if the design is trademarked. This makes sense. An issue worth considering, however, is whether a vector image file (i.e. EPS or SVG) of an uncopyrighted design can have its own copyright with regard to the vector data. In particular, sites such as seeklogo.com carry vector images of logos that almost certainly include logos in the {{PD-textlogo}} category. For these, there is the question as to whether converting an EPS from seeklogo.com to SVG would implicate copyright on the original EPS file. There is also the issue wherein vector images of fonts can be copyrighted in circumstances where a raster rendering would not (from what one understands); some of the info on the talk page for {{PD-textlogo}} may also be relevant. From what one can tell, it may be that there is no one clear answer that covers every situation and it may depend on the specific markup of a vector file and/or the specific design represented by the vector file data. Along these lines, one possibility to consider is adding something like the following to the "Simple designs" section before the "Fonts" subsection:

- Raster renderings (i.e. PNG images) of uncopyrighted simple designs can themselves be regarded as being uncopyrighted. For vector images (i.e. SVG files) of uncopyrighted simple designs, the question as to whether the vector representation has its own copyright is less clear; see the English Wikipedia copyright information about fonts and the {{PD-textlogo}} talk page for more information.

--Gazebo (talk) 04:38, 4 July 2014 (UTC)

- Any thoughts...can the above wording be improved?-it would seem useful to address the issue somehow. --Gazebo (talk) 09:08, 18 July 2014 (UTC)

Multilicensing with accepted and non-accepted licenses

Let's say that I want to dual-license an image, making it available under a version of cc-by-sa and cc-by-nc. Such a thing is explicitly permitted here (all we care about is that it has one Commons-acceptable license), but how would this be done from a technical perspective? For example, {{Cc-by-nc-2.0}} redirects to a speedy deletion template, a good idea in most cases, but very bad in an acceptable dual-licensing case. This page currently doesn't explain how this is done; it ought to give an explanation or (even better) a link to a technical help page explaining how to do this. Nyttend (talk) 00:14, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

- Some users create a cc-by-nc template in their userspace. See for example User:青子守歌/cc-by-nc. --Stefan4 (talk) 00:21, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think such standalone tags are not allowed (to reduce our housekeeping jobs). But User:青子守歌/own_work/license is OK. Nyttend, you can create a new multi-license tag like Template:GFDL or cc-by-nc-2.0 under Category:Multi-license license tags. Jee 02:37, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think that User:Jarekt has a bot which finds files which do not have any copyright tag at all. Does that bot find files which only use User:青子守歌/cc-by-nc? It would be convenient if it does. --Stefan4 (talk) 02:56, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think that tag is not used in any files. It is used only in the other tag I mentioned above. Jee 03:04, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think that User:Jarekt has a bot which finds files which do not have any copyright tag at all. Does that bot find files which only use User:青子守歌/cc-by-nc? It would be convenient if it does. --Stefan4 (talk) 02:56, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

- I think such standalone tags are not allowed (to reduce our housekeeping jobs). But User:青子守歌/own_work/license is OK. Nyttend, you can create a new multi-license tag like Template:GFDL or cc-by-nc-2.0 under Category:Multi-license license tags. Jee 02:37, 11 December 2014 (UTC)

Wikilink

The "Open Content - A Practical Guide to Using Creative Commons Licences" published on Meta and available here as PDF could be added in the "See Also" section. Normally I'd try a SoFixIt, but on a policy page + IANAL + only read a review on https://en.planet.wikimedia.org/ somebody else has to decide if that's a good idea.![]() –Be..anyone (talk) 07:58, 13 December 2014 (UTC)

–Be..anyone (talk) 07:58, 13 December 2014 (UTC)

Done, one witness posted no objection, there's now also a gallery. –Be..anyone (talk) 15:56, 7 February 2015 (UTC)

Done, one witness posted no objection, there's now also a gallery. –Be..anyone (talk) 15:56, 7 February 2015 (UTC)

BD-propagande picture

That's actually a minor issue, but why File:BD-propagande colour en.jpg is not shown by {{LM}} in some translated versions of this policy? It should since translated images exist --Nastoshka (talk) 10:43, 21 April 2015 (UTC)

only non-free-licensed exception

The site currently states

The following restrictions must not apply to the image or other media file:

- Use by Wikimedia only (the only non-free-licensed exceptions hosted here are Wikimedia logos and other designs which are copyrighted by the Wikimedia Foundation).

This seems to be not true, as I can not find any "Wikimedia logos and other designs" on Commons which are not under a free licence. So all of them are allowed without this exception. Therefor I'm suggesting to drop the part in parenthesis. --Nenntmichruhigip (talk) 16:02, 5 June 2015 (UTC)

- Some context here: wmfblog:2014/10/24/wikimedia-logos-have-been-freed/ --Jeremyb (talk) 16:16, 5 June 2015 (UTC)

- I've now removed the nolonger correct part. --Nenntmichruhigip (talk) 21:07, 22 June 2015 (UTC)

Image copyright violations on fair-m.hu

On this commercial site many images used seemly without regarding the rules and rights: www.fair-m.hu On its first (landing) page grabbed photographs from wikipedia and also from other community sites are in use. (eg.: http://www.fair-m.hu/assets/ingatlanok-hodmezovasarhely.jpg which is published originally on https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:H%C3%B3dmez%C5%91v%C3%A1s%C3%A1rhely,_Bankpalota_SF.jpg) I think this behaviour is unacceptable and against the rules of wikipedia and also against international and Hungarian laws. How can we inform the owners of the photographers?

- You can inform the uploaders (which is often the same as the photographer) on their talk pages. The image in question was uploaded to Wikimedia Commons by User:Pataki Márta, who might be interested in this image use. You can also inform the Web site that what they are doing might be against the law, they will often not be aware of that. Many people don't understand the difference between a free license and public domain. Of course, the site might have gotten permission to use the images without attribution, only the copyright holders would know for sure. --rimshottalk 22:17, 23 December 2015 (UTC)

A quick but not entirely accurate introduction

This edit caught my eye.

If a newbie cannot use the graphic safely it needs to go.

Yes- it is fine, to remove the gory detail and legal shenanigans for a panel designed for the unsure, and nervous. But it must err on the side of safety- so if it is wrong, what is wrong. Newbies are put off by thinking they have done it all correctly then having their work zapped.

Does the graphic need to be redrawn?

A little discussion please?ClemRutter (talk) 22:05, 26 January 2016 (UTC)

Ecxel's screenshots

Hello, can u help me? I want to upload some images from another project, can u check this page. Images from the page are ok for commons or not? Iniquity (talk) 16:35, 2 February 2016 (UTC)

- Please read the instructions on top of this talk page. Your question belongs here. --Nenntmichruhigip (talk) 17:33, 2 February 2016 (UTC)

Licensing of the images

In the Wikimedia Commons you can upload images with a free license(Share alike), with the ability to change/adapt image and use I'm commercial purposes. I'm at a loss why the image must have permission to use for commercial purposes and to change?

1. I know, that images on articles usually aren't in default size, so you change them. But, according to this: "In 2002, the court in the US case Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corporation ruled that it was fair use for Internet search engines to use thumbnail images to help web users find what they seek.", you may use smaller images.

2. Text from projects Wikimedia (I don't know about Wikinews) is published under free license, that warns text from using in commercial purposes. And Wikimedia is completely free, so why do images must have ability to use in commercial purposes.

So I propose to change the image upload rules, allow to unload images with the licenses that bans changes and using for commercial purposes

Ігор Пєтков (talk) 15:32, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

- 1. Thumbnails possibly, but Commons wants full size images. Secondly, fair use is U.S. law, and other countries might have less protection.

- 2. Wikinews is free just like Wikipedia. And yes, you can use that text for commercial purposes -- if you can't, the text would not be allowed on Wikipedia or Wikinews, just like here. CC-BY-NC text is not allowed there.

- 3. This requirement is not something that Commons can change; it is part of all Wikimedia projects and is mandated by the Foundation. See wmf:Resolution:Licensing policy. Note that Commons is specifically barred from using any fair use rationales. Both commercial use and the ability to make derivative works are part of the Definition of Free Cultural Works. Carl Lindberg (talk) 16:26, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

- Ігор Пєтков, please read Commons:Licensing/Justifications and Commons:Fair use, which explain the problems with non-commercial restrictions and why fair use does not apply to general-purpose media repositories like Commons. There are prominent links to both these pages from the policy itself. —LX (talk, contribs) 21:22, 16 February 2016 (UTC)

1923

I would like to upload a book on wikimedia for a further use on wikisource. Author died more that 70 years ago but the book has been published in France in 1923. Am i allowed to do so, due to the 1923 rule?

Thanks and Regards

--Bob isat (talk) 18:17, 19 March 2016 (UTC)

- Bob isat: Bonjour,

- Le copyright dépend de l'année de décès de l'auteur. Le livre est dans le domaine public aux Etats-Unis si l'auteur est mort avant 1936. Cordialement, Yann (talk) 21:37, 19 March 2016 (UTC)

- Yann:Bonjour Yann et merci pour votre retour.

L'auteur (en l'occurence Michel Corday) est mort le 12 Janvier 1937. Sachant que le roman qui m'occupe a été publié en 1923, ne puis-je donc pas l'uploader sur Commons, pour l'appeler ensuite sur Wikisource?

Merci pour votre aide.

--Bob isat (talk) 13:04, 20 March 2016 (UTC)

- Bob isat Bonjour, Dans ce cas, il vaut mieux l'importer sur Wikisource. Cordialement, Yann (talk) 14:12, 20 March 2016 (UTC)

Indian Army Licensing

Is the media released or posted in Indian Army website http://indianarmy.nic.in/ are free to be uploaded to Commons are per the their copyright policy. If yes what is the template? <bɾ> Copyright Policy of Indian Armyː http://indianarmy.nic.in/Site/FormTemplete/frmTempSimple.aspx?MnId=Gh8sw8nlH9TmK4BGh7xcKQ==&ParentID=KtP0cOB21+nPeAHRphT0OQ== --Krishna Chaitanya Velaga(Citizen of the RoIN) Talk 14:39, 3 May 2016 (UTC)

Including Public Domain in the options of licensing

When I post a photo, I would like to be able to release it in the Public Domain (PD). I understand there is a reluctance to implement that because in some countries Public Domain doesn't even exist. Well, if we look at things that way, then I suspect there are countries where the Creative Commons license is illegal or inapplicable. What are we doing with the Public Domain photos hosted at Wikimedia Commons? We can't use them in articles because in some countries PD is not even defined? So that should not be an argument against PD.

At very least, the creator should have the alternative of releasing their work with "dual licensing": Creative Commons or Public Domain, leaving the user the choice to use the work the whay they wish, and as allowed by the local laws. This is nothing new, I've seen programs released with dual licensing (GPL and a commercial license). Also I've seen public domain works and posting and using do not seem to be problematic out there in the world. — Ark25 (talk) 20:40, 29 May 2016 (UTC)

- What does public domain gain you over the {{Cc-zero}}?--Prosfilaes (talk) 22:51, 29 May 2016 (UTC)

- Oh, I haven't noticed that option until now, thanks! — Ark25 (talk) 10:28, 30 May 2016 (UTC)

Creation for template of Indian Air Force

I propose to create a template such as that is created for Indian Navy Template:Indian_navy, to license the images that uploaded which have been taken from the Indian Air Force Website. Because the site features the copyright statement asː

Material featured on this site may be reproduced free of charge in any format or media without requiring specific permission. This is subject to the material being reproduced accurately and not being used in a derogatory manner or in a misleading context. Where the material is being published or issued to others, the source must be prominently acknowledged. However, the permission to reproduce this material does not extend to any material on this site, which is explicitly identified as being the copyright of a third party. Authorisation to reproduce such material must be obtained from the copyright holders concerned. It can be viewed in the usage policy of the website.Krishna Chaitanya Velaga(Citizen of the RoIN) Talk 10:04, 23 May 2016 (UTC)

- Unless they explicitly say they are licensing it under a CC-BY license, we cannot assume that. The tag needs to have the licensing text as-is. The fact they don't mention derivative works might make some users nervous about the terms, though even derivative works generally "reproduce" expression so that could be implied there. Carl Lindberg (talk) 21:20, 25 May 2016 (UTC)

- The Navy licence doesn't appear to allow modifications, which is essential for the Commons. Hchc2009 (talk) 20:02, 26 May 2016 (UTC)

- @Krishna Chaitanya Velaga, Clindberg, and Hchc2009: {{Attribution-IAF}} already exists. Per the discussions on its talkpage (Carl Lindberg, you have a short memory :) ), the freedom of it seems to be disputed. Personally, I agree with Hchc2009 and think that the accuracy requirement is an NoDerivatives restriction – maybe the discussion should be revived in a request for deletion? FDMS 4 13:12, 4 June 2016 (UTC)

- The Navy licence doesn't appear to allow modifications, which is essential for the Commons. Hchc2009 (talk) 20:02, 26 May 2016 (UTC)

- Ah, right. The proposed template should be deleted then; that is a better one. "Accurate" usually refers to moral rights to me (don't make a misleading modification and claim it's the original, stuff like that) -- but I figured that is where there might be some opposition. Carl Lindberg (talk) 03:46, 6 June 2016 (UTC)

Yep. There are licences which require "accuracy" (i.e. not misleading anyone) but allow modifications. But equally many licences allow reproduction, but not modification and derivative works - these are different rights. The IAF doesn't seem to allow derivatives. Hchc2009 (talk) 06:30, 7 June 2016 (UTC)

- @Hchc2009: Actually, modification / derivative works are forms of reproduction -- you are reproducing some of the original expression in some form. A copyright license can certainly prevent those types of reproduction, but this one does not necessarily prevent them. The concentration on "accuracy" seems to point to moral rights in particular, which is OK. It's more a question if you read "reproduction" as more of strict duplication, or in the more general sense of any reproduction of the expression. It's not always an easy question, so there can be differing opinions. India's copyright law does include the concept of "adaptation", but that seems to be narrower than the concept of derivative works (which is not a term used in India's law). Rather that seems to be altering or abridging works for the needs of a different format -- seems to more often apply to literary, dramatic, and musical works. As part of the rights of copyright, it includes the right to reproduce the work in any material form including depiction in three dimensions of a two dimensional work or in two dimensions of a three dimensional work -- which would be a derivative work in the U.S. definition, but their law uses the term "reproduce" there. On the other hand, making "adaptations" and making "translations" are separately listed rights granted under copyright (with "translation" not having an explicit definition). Their law does not define "reproduce" either, though it does define "adaptation". So, the license they give is more a matter of how you interpret their wording -- they do allow reproduction in any format or media, which could imply "adaptations" as well as the quoted clause, and certain does seem to imply something beyond straight duplication. For graphic/artistic works, "reproduce" would seem to cover most stuff in their law anyways. But I can understand reading the term as being more restrictive, or at least ambiguous. Carl Lindberg (talk) 15:14, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

Help with image licensing

Hello. I'm here from English Wikipedia. Anyway, I've been communicating with a new user, w:en:User:Sandy Montoya, on my talk page, w:en:User talk:Gestrid about an article she's drafting, w:en:Draft:Scott Nute. She used images that she apparently uploaded to Commons (which is why I'm coming here instead of the English Wikipedia's counterpart) under the wrong license. At the moment, I'm not sure which license would be the correct one, but she says she has permission to use the images. I'm still communicating with her on the matter. Is there a template I can use to say they were put up under the wrong license and that the correct one will be up soon? Would it be best to delete the images so she can upload using the correct license? If it comes to deleting the images to re-upload them under the correct license, I'd rather that not happen until I've had a chance to notify the new user. Also, feel free to join the discussion on my talk page if you feel like you need to. -- Gestrid (talk) 01:33, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- @Gestrid: Hi, I tagged all their uploaded files as "no permission". The copyright holder of these files should send an email to the OTRS. Thanks, ★ Poké95 03:25, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- Thank you, Pokéfan95. I'll tell them to have the people who own the copyright to do that. -- Gestrid (talk) 14:11, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- How would he/she know who to contact, Gestrid, and why would the copyright owners do what they are asked – unless of course the editor has a w:WP:Conflict of interest? Justlettersandnumbers (talk) 14:21, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- I'm not entirely sure, Justlettersandnumbers, but she assures me she got permission. As I said, she's new to Wikipedia. It's also possible she herself has the evidence needed, but just didn't know what to do with it. Even I am confused by all the copyright policies, and I've been an editor on Wikipedia for several years. -- Gestrid (talk) 14:30, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- UPDATE: I've asked the editor if she has a w:WP:COI and, as a follow-up question, if she is being w:WP:PAID. -- Gestrid (talk) 14:38, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- UPDATE 2: The editor says they do not have a conflict of interest and they are not being paid. -- Gestrid (talk) 20:16, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- For Wikipedia in English, that is probably a good thing. For Commons, neither is relevant. We are glad to have people upload images for whatever reason (as long as the images themselves are in scope and properly licensed/PD), on free time or professionally. I hope you get the evidence (sent to OTRS or otherwise). The most common problem with "having permission" is having permission just for using the images on Wikipedia, not for releasing them under a suitable licence. --LPfi (talk) 13:08, 11 July 2016 (UTC)

- While that may be the case for images on Commons, the COI and PAID questions were concerning the draft the user is trying to make, not necessarily the images they tried to upload. As far as I can tell, Wikipedia doesn't have a problem with COI and PAID unless it has to do with an article. -- Gestrid (talk) 16:03, 11 July 2016 (UTC)

- For Wikipedia in English, that is probably a good thing. For Commons, neither is relevant. We are glad to have people upload images for whatever reason (as long as the images themselves are in scope and properly licensed/PD), on free time or professionally. I hope you get the evidence (sent to OTRS or otherwise). The most common problem with "having permission" is having permission just for using the images on Wikipedia, not for releasing them under a suitable licence. --LPfi (talk) 13:08, 11 July 2016 (UTC)

- How would he/she know who to contact, Gestrid, and why would the copyright owners do what they are asked – unless of course the editor has a w:WP:Conflict of interest? Justlettersandnumbers (talk) 14:21, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

- Thank you, Pokéfan95. I'll tell them to have the people who own the copyright to do that. -- Gestrid (talk) 14:11, 10 July 2016 (UTC)

Currency in Zimbabwe

I noticed we have Template:PD-ZW-currency which links to Zimbabwean copyright law from 1967; however, it seems Zimbabwe has a new law from 2004, and I am unable to find any similar clause limiting copyright on demonetized money and coins in the new law. Could somebody take a look and… either update the template, or IDK, nominate all Category:PD-ZW-currency images for deletion? --Mormegil (talk) 14:02, 29 July 2016 (UTC)

- It would seem they would probably get the government copyright, which seems to be 50 years from publication (article 15). Carl Lindberg (talk) 19:42, 30 July 2016 (UTC)

- Or somebody could send a mail to the authorities to check weather the old copyright law still applies until that date and so the currency is still PD or not.--Sanandros (talk) 20:37, 30 July 2016 (UTC)

- The old law only said banknotes were PD when they were demonetized. Carl Lindberg (talk) 02:23, 31 July 2016 (UTC)

Copyrighted before 1923 whether published or unpublished

Copyrighted before 1923 whether published or unpublished. Even if a work was unpublished but was labeled with a copyright notice, it is in the public domain. The same would hold true for works mailed to the copyright office prior to 1923 to prove copyright. All the rules on the page licensing page use the word "published". Unpublished but distributed copies, such as those distributed by news agencies and distributed by publicity departments before 1923 are also in the public domain. --Richard Arthur Norton (1958- ) (talk) 20:01, 2 August 2016 (UTC)

- If a work was registered with the copyright office while unpublished, yes, that started the copyright clock. This is mentioned on the {{PD-1923}} template. I don't think putting a copyright notice on an unpublished work would automatically start the clock -- I think the law just says when published with notice, which was general publication, not limited publication. But it would be rare to put a notice on an unpublished copy (or one not meant for publication), so it's probably safe to assume that if one exists, then the copyright clock started at that year. Distribution, most of the time, would be the moment of general publication, so I'm not sure what you mean by "unpublished but distributed" distinction.

- The issue was that unpublished works were not covered under federal copyright protection, but rather per-state common-law protection -- which could be unlimited in duration, but was much weaker. At the moment of general publication, common-law protection was extinguished and the federal rights took over, which had a limited duration but was much stronger with more explicit penalties. If an author wanted the stronger protection, they could register an unpublished work with the Copyright Office, which would then also stop common-law protection and become federally protected. I'm not sure the law allowed any other mechanism to switch over from common-law protection to federal protection. Carl Lindberg (talk) 20:51, 2 August 2016 (UTC)

- I'm pretty sure that back in the day, a copyright notice on an unpublished work would have at least set the clock once the work was published. There was one movie that had a copyright notice that was 10 years too earlier, and the court ruled that that's when the clock started for renewals; I suspect if "unpublished" authorized copies were floating around with a copyright notice, that copyright notice would be taken as gospel. Modern courts seem more generous, though, even ruling on the same laws.--Prosfilaes (talk) 02:31, 3 August 2016 (UTC)

- Yes, once published, if an erroneous year is there in the notice which is earlier than actual publication, then that becomes the starting date. If dated more than one year later than actual publication, then the entire notice was considered invalid. But if a work only saw limited publication, technically I don't think the presence of a copyright notice would matter. It's just that with a notice, the presumption is that it was published, and it would be rare to impossible to identify such a work (unpublished and unregistered) today, I'd guess. Limited publication was in some courts was defined as distribution to a limited set of people for a limited purpose with no further right of distribution -- all three had to be satisfied -- though some circuits had a slightly different definition. But overall yeah, I'd say the presence of a copyright notice would be all the evidence we need for PD-1923. Carl Lindberg (talk) 04:41, 3 August 2016 (UTC)

Invitation to copyright strategy discussion

Hello! I'm writing from the Wikimedia Foundation to invite you to give your feedback on a new copyright strategy that is being considered by the Legal Team. The consultation will take the form of an open discussion, and we hope to receive a wide range of thoughts and opinions. Please, if you are interested, take part in the discussion on Meta-Wiki. JSutherland (WMF) (talk) 23:25, 29 August 2016 (UTC)

People in Pictures

Is there a special license to obtain before uploading pictures that I personally took of people in groups, for example a group picture of people attending a conference, or of people at a public event? Drbones1950 (talk) 02:35, 18 September 2016 (UTC)

- Not from a copyright perspective, but you should read Commons:Personality rights. —LX (talk, contribs) 15:55, 18 September 2016 (UTC)

Unfortunately, the example we give of a free image is not free. The sculpture in the photo is from 1989 and there is no FOP in Lithuania. . Jim . . . . (Jameslwoodward) (talk to me) 09:55, 10 October 2016 (UTC)

நான் சொந்தமாக எடுத்து இணைக்கும் படங்கள் எந்த வகையில் Copyright violations ஆகிறது?

நான் சொந்தமாக எடுத்து இணைக்கும் படங்களை ஏன் நீங்கள் நீக்குகிறீர்கள். அவை எந்த வகையில் Copyright violations ஆகிறது. புதிதாக யாரும் கட்டுரையோ படங்களையோ இணைக்கூடாது என்று நினைக்கிறீர்களா? எங்களுக்கு வேறு வேலை வெட்டி இல்லை என்றா நினைத்துக்கொண்டு இருக்கிறீர்கள்.... நீங்கள் அனுப்பிய இந்த செய்திக்கு என்ன பொருள். எதற்க்காக last warning. உடன் பதிலை சொல்லுங்கள் திரு. ஆலன்O.

"Hello Velu66. It has come to our attention that you have uploaded several files that are copyright violations. You have done so despite requests from editors not to do so, and despite their instructions. See Commons:Licensing for the copyright policy on Wikimedia Commons. You may also find Commons:Copyright rules by subject matter useful.

This is your last warning. Continuing to upload copyright violations will result in your account being blocked. Please leave me a message if you have further questions." — Preceding unsigned comment added by Durai.velumani (talk • contribs) 13:34, 25 October 2016 (UTC)

PD-old-100

If as stated in {{PD-old-100}} the author has been dead for more than 100 years, and assuming this is the correct reason, it must has been published before 1916 (posthumous publications follow different rules, but the point will be essentially the same). Thus, the work is PD in the US, since "Copyrights prior to 1923 have expired" (see Cornell reference) - so why is there a warning saying "You must also include a United States public domain tag to indicate why this work is in the public domain in the United States." ? Michelet-密是力 (talk) 13:06, 10 November 2016 (UTC)

- If it was never published until the 1900s, it could still have a U.S. copyright. Before 1978, in the U.S. there was no copyright limit on unpublished works (they were common-law copyright -- U.S. federal copyright protection started upon publication). So while really unlikely, it is possible for a very old work to still be under copyright protection. If first published after 1922 and before 2003, it is theoretically possible at least. The Cornell link goes over those possibilities. Carl Lindberg (talk) 14:01, 10 November 2016 (UTC)

- Indeed, same thing in France for example, and everywhere under the Berne convention : works are protected only insofar as they are published, be it by the author or after his death. And the protection of posthumous works (if any) always start at the publication date. But that is not the point:

- If the template is relevant, then its statement is true : "This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 100 years or less." And that is the reason of its being PD.

- In this "PD because Death>100", this reference to the author's life is only relevant if the work has been published while the author was living. Otherwise the formulation would be incorrect, you would have to mention the publication date irrespective of the author's date.

- Therefore, as long as the template states the correct reason, the file is PD in the US. And if it is incorrect in the US, it is incorrect elsewhere as well.

- Posthumous publications need special treatments whatever the country. So, why bother mention anything about the US ? Michelet-密是力 (talk) 10:32, 11 November 2016 (UTC)

- The term of protection of posthumous works under the Berne Convention is life+50. Last I checked, Canada, for one, gave posthumous works no longer protection. It's possible the template needs specification to non-posthumous works and maybe a list of countries that don't give extra time to posthumous works, but it shouldn't say nothing about the fact it doesn't always apply in the US and many other countries.--Prosfilaes (talk) 02:16, 12 November 2016 (UTC)

- Agreed with Prosfilaes... I don't think there is anything in the Berne Convention which automatically has unlimited copyright for unpublished works. It mandates 50pma, but that would seem to be it, regardless of being published (or the distinction of "making available to the public", which can be different than publication, which is used for anonymous works -- but even then there is a limit based on date of creation). Even the EU no longer has any infinite limits, really -- other than the 25-year publication right, which is not owned by the author but rather the publisher, and it's not clear that would be recognized outside the EU (nothing in the Berne Convention about that). The U.S. no longer has infinite limits -- only the special case of pre-1978 works published between 1978 and the end of 2002 could have a longer term than the normal 70 pma or (for corporate works) 120 years from creation. If works were still unpublished as of 2003, their copyright went poof unless still within 70pma. Carl Lindberg (talk) 05:50, 12 November 2016 (UTC)

- Indeed, same thing in France for example, and everywhere under the Berne convention : works are protected only insofar as they are published, be it by the author or after his death. And the protection of posthumous works (if any) always start at the publication date. But that is not the point:

{{PD-old-100}} obviously.

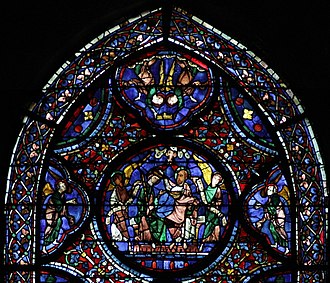

Surprise - Why in the world would Commons tell me "You must also include a United States public domain tag to indicate why this work is in the public domain in the United States"  ??? It's been hanging there for eight centuries...

??? It's been hanging there for eight centuries...

Context : My concern comes from my using {{PD-old-100}} on the Chartres stained windows, where the comment "You must also include a United States public domain tag to indicate why this work is in the public domain in the United States" is ludicrous : when America was discovered, these windows were two and a half centuries old ! Obviously there is no need to add anything, and the comment is irrelevant - at least in that case. There is nothing else I "must include".

- My point is that the remark ""You must also include a United States public domain tag to indicate why this work is in the public domain in the United States"" is irrelevant in all cases, as long as the {{PD-old-100}} is correctly used.

The Berne Convention (BC) only protects published works, and says little about posthumous works (which are not "works published with the consent of their authors", -BC§3(3)- ). Indeed, since it is of general interest to have posthumous unpublished works both published and protected, laws will give some protection to the "discoverer", but it is not directly related to the BC. And anyway, that protection never exceeds that of works published by their authors (Prosfilaes's remark).

- Your consideration of posthumous works is relevant as far as PD is concerned for Commons, but (1) the problem is not limited to the US, and (2) if there actually is such a problem, the tag states an incorrect reason for the work to be PD, so the tag is incorrect in the first place. Unless posthumous works are given no protection at all (and that by itself is dubious and worth mentioning), the publication date should at least be mentioned as the reason why the work is PD in its country of origin. Repeat : in those cases where an additional tag is actually needed, the {{PD-old-100}} alone is incorrect, and should be changed or completed even in the country of origin.

In my opinion the US warning is irrelevant and can altogether be suppressed, without changing the accuracy of Commons licensing tags - if it's truly {{PD-old-100}} anywhere, "why this work is in the public domain in the United States" is that the author has died more than a hundred years ago, so the "US tag" called for should be {{PD-old-100}} as well - it's already there.

To take into account your concern about posthumous works, and state the correct reason why such a work is PD, the tag can be rephrased so as to include such concern :

For more than a hundred years, both the work has been published, and its author(s) has died. This work is therefore in the public domain in its country of origin, and any other countries where the copyright term is under those limits.

It wouldn't change anything substantial in the Commons database : if the author has died more than 100 years ago, but the work is posthumous and was published less than 100 years ago, then its PD status should be separately checked and asserted anyway - which is already the case, due to that warning. The "worst case" would be that the statement is false and the work is PD anyway. But in that case, once you've checked and found that the tag is incorrect, the hard work is done and you know how to correct the tag anyway (just do it).

Michelet-密是力 (talk) 08:25, 12 November 2016 (UTC)

- Yes, if a work was actually published that long ago, it's fine for the U.S. It's just that PD-Old-XXX does not definitively say that the work was actually published -- in many countries it can become PD without being published -- so that tag alone is not necessarily enough. That is why there are combined tags like {{PD-old-100-1923}}, {{PD-old-70-1923}}, etc., which also indicate publication before 1923, and the better one of {{PD-old-auto-1923}} where you can supply the year the author died and the number will adjust as appropriate. Commons policy is that works must be public domain in the country of origin and the United States, which is why the U.S. tag is more necessary than those of other countries. In virtually all cases, PD-old-100-1923 would also be valid, but you can find a theoretical case where PD-old-100 was valid but PD-1923 was not. That is all the tag is saying (and the wording is copied from all other PD-old-XXX tags). U.S. law has a particularly convoluted definition of "publication", especially before 1978 when it was defined by case law, so it is prudent to still have the separate tag.

- The Berne Convention protects all works, published and unpublished. There are several clauses in there which deal with unpublished works. The term is 50pma regardless. It just considers the right of first publication particularly important, so it uses that definition in some clauses. But there is nothing in the Berne Convention regarding publication which changes the term of the copyright (outside of anonymous/pseudonymous works), whereas it does in United States law. Some countries may additionally have longer protection for unpublished works -- but that would mean the PD-old-100 tag is incorrect in the first place, as it would not serve for the country of origin. You seem to be saying that is true for all countries, but it is not (far from it) and is definitely not mandated by the Berne Convention. Carl Lindberg (talk) 16:19, 13 November 2016 (UTC)

- "You seem to be saying that is true for all countries" : no, I'm saying that in no country the term is >100years after publication in the case of posthumous works (A => B dos not mean B => A). Michelet-密是力 (talk) 10:18, 19 November 2016 (UTC)

OK. Given the argumentation above, is it OK to make that change on the {{PD-old-100}} text?

For more than a hundred years, both the work has been published, and its author(s) has died. This work is therefore in the public domain in its country of origin, and any other countries where the copyright term is under those limits.

- The template is 100pma (100 years after the author's death), which is (nominally) the term in Mexico. The template does not indicate anything at all about publication -- in many countries, unpublished works expire at 70pma etc. regardless. A separate U.S. tag is technically needed to indicate publication. If you want to indicate publication as well, just use {{PD-old-100-1923}} and don't use this tag. But using PD-old-100 and {{PD-US-unpublished}} together may also be a somewhat common pairing. I would not agree to any change in the wording. Carl Lindberg (talk) 22:35, 19 November 2016 (UTC)

Free license only for lower quality version

This paragraph (previous edit summary refers to this section on VP/C) needs to be discussed again, judging by the arguments on COM:AN. Oliv0 (talk) 09:39, 9 November 2016 (UTC)

- 1/ The formulation was poor, but the legal aspect is clear.

- An author can license both his work and its derivatives. In that case, if a photographer takes a photograph, publishes a high resolution and licenses only "copies under 300px in any direction" as being free, then only copies under 300px in any direction are free under that condition. Nobody can say that because the author has (1) allowed low-quality copies, and (2) published a high quality version, that (3) he has lost author's rights on the high quality version, which would allow it to be freely copied. For author's right, anything that is not formally released is retained (this is an author's right problem, not a "lack of copyright mention").

- But the formulation "Even if higher resolution file of a work is available in a different source, Commons (as a matter of courtesy/ethics) will not host such files if they are not explicitly tagged with a free license." is misleading, since for instance a museum may state this kind of restriction on photographs of paintings that are PD in the first place. You must own the author's right in order to be able to state restrictions. And anyway, it is not a matter of courtesy, it is a legal point: if you go beyond the author's will you are outside the law (and may be punished for that).

- I would suggest :

- A free license associated to a published file applies only to that specific publication, not to the work it represents. As long as the work itself is protected, the published license cannot be extended to a higher resolution file of the same work, that would for instance be available in a different source, even when the higher resolution publication is made without any explicit restriction.

- The phrasing could probably be fine-tuned, but the idea is correctly stated. Michelet-密是力 (talk) 11:10, 11 November 2016 (UTC)

- 2/ As for the meaning of "CC-BY-SA-3.0 with some restrictions: "exact citation (year of publication, picture number), and size under 300 px in both directions"" : the author authorizes a CC-BY-SA-3 on 300x300 versions of his file, not on the file itself. You may therefore make (by yourself) a 300x300px version, and tag it with the CC-BY-SA-3, conforming to the author's will.

- On your file, you may remove the ", and size under 300 px in both directions" clause, since your file is conform to that. After that, you may even legally enlarge the picture to a 3000x3000, as long as you can prove that it is a derivative from the 300x300, not from the original file, but this would be awkward and is best avoided, of course.

- The part "exact citation (year of publication, picture number)" is to be respected anyway, whatever the license.

- Michelet-密是力 (talk) 11:17, 11 November 2016 (UTC)

Discussion

- The statement "A free license associated to a published file applies only to that specific publication, not to the work it represents." is simply not true. The policy text does not need changing and the deletion did not actually affect that policy text.

- Oliv0 you are confusing two things. The policy refers to "while applying stricter terms to higher quality versions" with the implicit assumption that those stricter terms are documented off-Commons along with this higher-quality version. For example, a higher quality version at a stock photo website with "All rights reserved" and very restrictive usage terms upon payment of a fee. What the policy does not describe is authors writing such terms onto the Commons File Description page in an attempt to make a previously free CC license no longer free. If the File Description page says, effectively, that high-resolution versions of this work-of-copyright are not free then that means the author hasn't actually released the work-of-copyright with a genuinely free license.

- In other words, when you release a work with a free license we will document that free license. What you do with versions of that work on other websites is none of our business. You can try to charge for high-quality/resolution versions if you like. But what Commons won't do is to acquire that higher-quality/resolution version and upload it here unless it is clearly labeled with a free license. There are just too many legal doubts that two random files on the Internet are actually the same work-of-copyright. -- Colin (talk) 15:49, 16 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Colin: "A free license associated to a published file applies only to that specific publication, not to the work it represents" can be wrong for CC but right in general for a non-CC free licence "BY-SA + low-res", that is why I said in that RFD that "allowing a file scanned at some size and not another file scanned at another size still seems to fit all of the definition of a "free license" for the file allowed" (link from COM:L), and that "the copyright holder's intentions" advocated by COM:L are "certainly better respected if the license is rephrased not to be contradictory [= to non-CC "BY-SA + low-res"] than if no freely distributable version is left.". Oliv0 (talk) 16:43, 16 November 2016 (UTC)

- In general, a copyright owner should be able to license their own work (or a portion of their own work) however they like. In that case, the "work" would be the chunk of copyrightable expression that they own, that they wish to license, as identified by the copyright owner. So, I certainly feel that an author can license just a lower-resolution version (though they cannot mandate that nobody can enlarge that particular version -- just that they can't assume the same license on a higher-resolution version found elsewhere). However, Creative Commons came out with a very (*very*) odd decision on that matter, where they say they "encourage" this lower-res licensing but say that it may not be legally enforceable everywhere -- that a copyright owner can only license the entire, full work. That may be based on the wording of the Creative Commons license, but I have never understood their interpretation -- to me, a copyright owner can partition a work however they like, so long as there is copyrightable expression they own in the result, and just license that. However, given the CC statement, we have chosen to be ambiguous as well, thus the edit. Now, if someone worded their restriction such that you are not allowed to enlarge the lower-res version that they license, well then that interferes with derivative works and would be a non-free addition to the license -- it is more than simply defining the "work", it is restricting what you can do with it, and would be a modified license. Carl Lindberg (talk) 21:24, 16 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Clindberg: on this last point what I said in that RFD about "the copyright holder's intentions" advocated by COM:L was that "the aim of the [low-res restricted] license is a limit of quality so it refers to the original size scanned, which allows further derivation to bigger sizes since this does not improve the image quality". Oliv0 (talk) 07:32, 17 November 2016 (UTC)

- I can also add here what I said on AN: contrary to the idea that COM:L implicitly means "stricter terms to higher quality versions" are given on an external site, so that giving on Commons a free license with such stricter terms can still be forbidden, I think COM:L explicitly says that "hosting only the lower quality version" is allowed, and that respecting a restriction made on an external site while forbidding the same restriction made explicitly on Commons makes no sense. Oliv0 (talk) 08:55, 17 November 2016 (UTC)

- Wrt you last sentence, it isn't as daft as it sounds. An external site can say things we have no control over. Images can be licensed under different terms elsewhere. For example, a user could upload their image here with CC BY-SA and upload what appears to be the same image to Flickr with CC BY-SA-NC. It isn't straightforward for us to prove both images are the same work-of-copyright. The "respect the copyright holder's intentions" clause is more concerned with the fact that CC/WMF misled copyright owners for years, and it would seem particularly unkind if we were to take advantage of that and acquire these higher-resolution images based on a misunderstanding of WMF's own making. -- Colin (talk) 10:15, 17 November 2016 (UTC)

- I can also add here what I said on AN: contrary to the idea that COM:L implicitly means "stricter terms to higher quality versions" are given on an external site, so that giving on Commons a free license with such stricter terms can still be forbidden, I think COM:L explicitly says that "hosting only the lower quality version" is allowed, and that respecting a restriction made on an external site while forbidding the same restriction made explicitly on Commons makes no sense. Oliv0 (talk) 08:55, 17 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Clindberg: , I don't understand your statement that CC "encourage" copyright owners to "licence just a lower-resolution version". I think both CC and WMF used to encourage this (there were links in the old discussion) and that's very poor of them, but their current FAQ does not encourage that or even claim it is possible. What they claim to "support" is releasing a lower-resolution version + making the "work" availble under CC, and then arranging quite separate contracts for the purchase/usage of any high-resolution file. CC made it quite clear to us that their licence applies to a "work of copyright" and also that the Definition of Free Cultural Works that Commons is built on similarly considers the "work of copyright", not individual files, photographs, recordings, etc. While I agree with you that a copyright owner may create a licence for a file, photograph, recording, etc, that is not the same as what CC and Commons are built upon. For example, when I buy a DVD then Disney licence me to play that recording in my home, but not to play it in public or to make copies of it, and I gain no permission to their master copy of the movie. It could be possible to design a file-based licence scheme for JPGs and such, perhaps using digital signatures, though that might be difficult without some kind of DRM which most free-culture advocates disaproove. So I think we are stuck with the "work of copyright" scope of any free licence that CC applies to or that can be used on Commons. I believe the image Oliv0 was concerned about comes from a book and that image can be scanned and uploaded here at whatever resolution the person scans it. But it turns out the photographer wanted to restrict that resolution to thumbnail size. Thus that restriction did not permit the "work of copyright" to be free. -- Colin (talk) 08:46, 17 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Clindberg: on this last point what I said in that RFD about "the copyright holder's intentions" advocated by COM:L was that "the aim of the [low-res restricted] license is a limit of quality so it refers to the original size scanned, which allows further derivation to bigger sizes since this does not improve the image quality". Oliv0 (talk) 07:32, 17 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Colin: -- OK, I guess "encourage" is a bit strong -- they say For example, you may publish a photograph on your website, but only distribute high-resolution copies to people who have paid for access. This is a practice CC supports. But, that does not explicitly say that the higher-resolution version would still not be covered under the free license once access is paid for, just that there could be an additional contractual restriction be put under the hi-res version at that point. I firmly believe that the author gets to choose the "work of copyright" and can license just that portion. If they make a painting, they can choose to only license the left half, or something like that. They are choosing the content which is being licensed, and that is the "work". I have seen some conjectures that uncropped versions of newspaper photos in archives may be an issue -- the portion originally published may be PD, but the uncropped portions may not be. When I think about what "work" means for photographs though, it could get messier for low vs high resolution versions, and maybe I understand CC's position a bit more. For a photograph, the copyrightable expression is typically in the angle, framing, timing, lighting, etc. -- aspects attributable to the photographer, and *not* the actual subject matter. So for snapshots, you may argue that all of those copyrightable aspects are present in the low-resolution version just as much as a high-resolution version, and as such the license on the low-resolution version gives you the same license to that same expression in the higher-resolution one. All of the extra detail in the hi-res version would not be copyrightable expression, thus all of the expression is still licensed. For a painting, I would firmly say a lower-res version license would be just fine -- a higher resolution version would contain a lot more of the original expression than a low-resolution one, and all that extra expression is still copyrightable, so I think an author would be OK there. And for a photographer who additionally controlled the subject matter -- they may have a stronger argument than a normal snapshot (though even then, if just selection and arrangement copyright, that may also be present in the lo-res version). So, that may be CC's caution there -- but it's an aspect not really tried in court so it may be hard to say. And subtle differences in wording can make a license non-free, versus wording which is just trying to define which expression is licensed vs that which is not. Carl Lindberg (talk) 15:56, 18 November 2016 (UTC)

- Carl there were several analogies discussed in the years-ago debase about what makes a separate work of copyright. Such as cropping a photo or the chorus of a song or one episode of a series or the trailer of a movie. And there is the complication that different jurisdictions may treat things differently. I can see that if someone in Photoshop Lightroom does "Export at 4000px" and then "Export at 500px" then it is hard to argue the resulting JPGs are different works of copyright -- after all, media wiki and other web sites frequently resize and crop images automatically. But there is a complication for two apparently similar photos, that we don't know how they were made and even if they came from the same negative/raw file. Photographers may release to their clients proofs, early drafts, in low resolution for them to review and choose which to buy. They may then do more work on the chosen frames such as retouching skin blemishes, altering colours, etc, which is likely to be a creative act enough to generate a new work of copyright. Then the tiny proof and the finished high-resolution image are separate works. I don't think we get many paintings on Commons that are not themselves out-of-copyright. So the conclusion from the debate for us was that (a) photographers would be unwise to think that they can be confident to keep their high-resolution image safe from someone trying to apply a CC licence they thought only applied to the low resolution image -- that might not work everywhere and (b) Commons can't be confident that they are the same work-of-copyright so best to avoid upload and (c) photographers were historically misled by CC/WMF. My personal feeling is that using analogies is dangerous because it is an attempt to rationalise the law from one's own amateur understanding -- when all that matters is what judges somewhere have decided, even if you think it is irrational. And none of this gets tried in court. So the best we can do is take the "advice" from CC/WMF-legal. -- Colin (talk) 18:23, 18 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Colin: Yes, but that is conflating what could be a derivative work (amount of copyrightable expression added to existing work) versus a partitioning of the work by the original author, and is not the same thing. I.e., is there a way the author can partition their work such that version B still contains copyrightable expression not found in version A -- in which case they can freely license version A as a "work", but still not license version B. Somebody else cropping a work would not create a new derivative work -- the license remains the same as the original. But the original author making a crop, then only licensing the crop, that can be OK -- the crop is licensed afterwards but the full original is not, presuming the original contains copyrightable expression not present in the crop. If it does not, then licensing the crop also has the effect of licensing the original. So, that is the key question -- where countries draw the line on what exactly is the copyrighted expression. For a painting, a crop would be no question -- the portions not seen in the crop are still separate copyrightable expression, so you cannot use the original based on a license of the crop. For a photograph, it may depend much more country-by-country -- a court could decide that the angle, framing, etc. was identical between the two, and thus all expression was licensed via the cropped version. I do think that could be a real issue now that I think about it, and we shouldn't be too sure -- but also, since it's possible a judge would allow that type of restriction, we should probably follow those wishes. But we probably should repeat the CC warning. I think I originally read their opinion as being based on what makes a derivative work, but now I think that interpretation is wrong -- it is more a matter if the author can actually make a version which contains only a subset of the copyrightable expression -- that may depend on the type of work, and is perhaps less likely for photographs. Carl Lindberg (talk) 21:48, 18 November 2016 (UTC)

- A photographer often makes technical choices to get a sharper image, this is a subset of the copyrightable expression which is lost in low-res. Oliv0 (talk) 07:51, 19 November 2016 (UTC)

- A possibility... but if there is only one aspect, that may not be enough. For the U.S. at least, it's not simply that a choice was made -- there has to be creativity involved. For similar reasons, the U.S. will generally not copyright based on a color -- the author was going to choose *some* color, and the choice is arbitrary (aesthetic attractiveness is not a copyrightable aspect), so that aspect is not copyrightable in a drawing -- it would be based on the actual lines drawn. And in this area, very small details matter, as I'm guessing the judge would be looking for a way to rule in the author's favor (the general trend in such cases), but there may be arguments in favor of all expression being licensed in certain cases. Carl Lindberg (talk) 00:37, 20 November 2016 (UTC)

- A photographer often makes technical choices to get a sharper image, this is a subset of the copyrightable expression which is lost in low-res. Oliv0 (talk) 07:51, 19 November 2016 (UTC)

- @Colin: Yes, but that is conflating what could be a derivative work (amount of copyrightable expression added to existing work) versus a partitioning of the work by the original author, and is not the same thing. I.e., is there a way the author can partition their work such that version B still contains copyrightable expression not found in version A -- in which case they can freely license version A as a "work", but still not license version B. Somebody else cropping a work would not create a new derivative work -- the license remains the same as the original. But the original author making a crop, then only licensing the crop, that can be OK -- the crop is licensed afterwards but the full original is not, presuming the original contains copyrightable expression not present in the crop. If it does not, then licensing the crop also has the effect of licensing the original. So, that is the key question -- where countries draw the line on what exactly is the copyrighted expression. For a painting, a crop would be no question -- the portions not seen in the crop are still separate copyrightable expression, so you cannot use the original based on a license of the crop. For a photograph, it may depend much more country-by-country -- a court could decide that the angle, framing, etc. was identical between the two, and thus all expression was licensed via the cropped version. I do think that could be a real issue now that I think about it, and we shouldn't be too sure -- but also, since it's possible a judge would allow that type of restriction, we should probably follow those wishes. But we probably should repeat the CC warning. I think I originally read their opinion as being based on what makes a derivative work, but now I think that interpretation is wrong -- it is more a matter if the author can actually make a version which contains only a subset of the copyrightable expression -- that may depend on the type of work, and is perhaps less likely for photographs. Carl Lindberg (talk) 21:48, 18 November 2016 (UTC)

- Carl there were several analogies discussed in the years-ago debase about what makes a separate work of copyright. Such as cropping a photo or the chorus of a song or one episode of a series or the trailer of a movie. And there is the complication that different jurisdictions may treat things differently. I can see that if someone in Photoshop Lightroom does "Export at 4000px" and then "Export at 500px" then it is hard to argue the resulting JPGs are different works of copyright -- after all, media wiki and other web sites frequently resize and crop images automatically. But there is a complication for two apparently similar photos, that we don't know how they were made and even if they came from the same negative/raw file. Photographers may release to their clients proofs, early drafts, in low resolution for them to review and choose which to buy. They may then do more work on the chosen frames such as retouching skin blemishes, altering colours, etc, which is likely to be a creative act enough to generate a new work of copyright. Then the tiny proof and the finished high-resolution image are separate works. I don't think we get many paintings on Commons that are not themselves out-of-copyright. So the conclusion from the debate for us was that (a) photographers would be unwise to think that they can be confident to keep their high-resolution image safe from someone trying to apply a CC licence they thought only applied to the low resolution image -- that might not work everywhere and (b) Commons can't be confident that they are the same work-of-copyright so best to avoid upload and (c) photographers were historically misled by CC/WMF. My personal feeling is that using analogies is dangerous because it is an attempt to rationalise the law from one's own amateur understanding -- when all that matters is what judges somewhere have decided, even if you think it is irrational. And none of this gets tried in court. So the best we can do is take the "advice" from CC/WMF-legal. -- Colin (talk) 18:23, 18 November 2016 (UTC)